Few people who lived and worked along the Canal could imagine building a life without the mule. Mules, it is said, were the engines of the Canal. Or put another way, the workhorses

moving coal from Mauch Chunk (present-day Jim Thorpe) to Bristol.

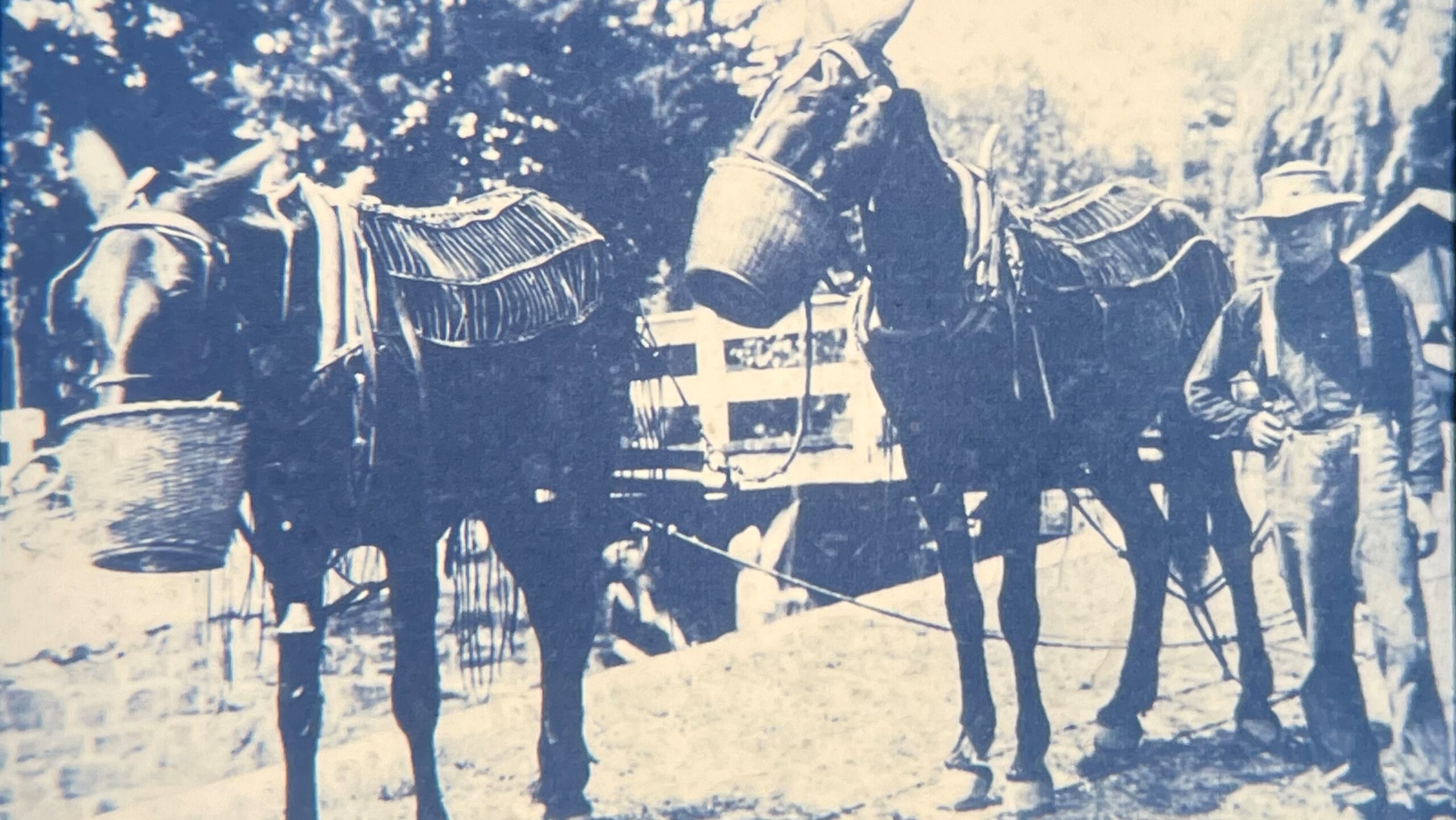

Mules—The Heart of the Canal

Favored by the founding fathers of our country, the mules established a stellar reputation when they came to the new world. Spanish missions used mules in their western North American missions in the early 1700s. George Washington, an avid farmer, became interested in utilizing mules and imported two male donkeys from Spain to begin a breeding program.

Favored by the founding fathers of our country, the mules established a stellar reputation when they came to the new world. Spanish missions used mules in their western North American missions in the early 1700s. George Washington, an avid farmer, became interested in utilizing mules and imported two male donkeys from Spain to begin a breeding program.

When the King of Spain and Marquis de Lafayette, both close friends of Washington heard of the new president’s breeding efforts, they also sent male donkeys to increase the stock. These donkeys from Spain and Andalusia were prized for their size and were called mammoth donkeys.

A mule is the asexual bi-product of breeding a female horse or mare with a male donkey or jack. Washington already owned mares to breed with these donkeys and eventually had more mules than horses on his estate.

The interest in mules spread throughout the South as Washington promoted using these animals in agriculture, even campaigning one of his donkeys to breed with mares. Thomas Jefferson also became a convert and soon had a breeding program and his own mules on the grounds of Monticello.

Man and Mule

Mules were put to work across America. They were used in agriculture, construction, mining, Continued on following page and transportation. These hardy equines pulled wagons, carriages, and canal boats.

So, when commerce on the Delaware Canal began, mules were the logical choice. From the perspective of the canal boat operator, mules had several distinct advantages. They had a sturdy constitution and were not prone to health problems. They could work long hours, perhaps slower than a horse, but they would keep going. The structure of the mule’s hoof increases its stability, and mules have fewer foot-related problems than horses. And mules seem to be calmer, exhibiting more common sense than a horse. According to author Rinker Buck, who wrote a book about his experience retracing the Oregon Trail in a covered wagon pulled by three mules, “Mules have a larger cranial capacity and thus larger brains than horses—a gift from their feral, burro side—and they ponder things a lot more.”

So, when commerce on the Delaware Canal began, mules were the logical choice. From the perspective of the canal boat operator, mules had several distinct advantages. They had a sturdy constitution and were not prone to health problems. They could work long hours, perhaps slower than a horse, but they would keep going. The structure of the mule’s hoof increases its stability, and mules have fewer foot-related problems than horses. And mules seem to be calmer, exhibiting more common sense than a horse. According to author Rinker Buck, who wrote a book about his experience retracing the Oregon Trail in a covered wagon pulled by three mules, “Mules have a larger cranial capacity and thus larger brains than horses—a gift from their feral, burro side—and they ponder things a lot more.”

Buck also admired the strong constitution of the mule. “Draft horses are too highly bred and, at almost a ton apiece, too heavy for long wagon journeys. They have stamina for only about 10 to 15 miles a day, have tremendous appetites, and cannot last very long without water or in the extreme heat of the deserts. Draft mules, however, weigh about 700 pounds less, can go long distances without water and barely perspire in the heat.”2

For the Canal Boatmen, mules were a perfect fit. They were calm, smart, and could work long hours without needing a rest. The tough

skin of this equine helped protect them from harness sores even after an 18-hour day.

Outfitting a Canal Mule

Canal boatmen purchased most of their mules from the company operating the Canal. For the Delaware Canal, that company was the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company. Boatmen would also buy the harness and other supplies from Lehigh Coal. The company would then deduct these expenses from the captain’s pay.

The Delaware Canal Journal describes the sale of young mules that the company would import from Kentucky and Missouri. According to one boatman, Grant Emery, “The Kentucky

mules were better, or fancier looking, but they didn’t hold up as well. I know my people were always Missouri mule men.”1

Once the young mule was purchased and fitted for a harness, they were shod and tattooed with a number on the sole of a front foot. That number was used not only to identify the owner of the mule but to ensure the company could track and charge the boatman for the cost of the animal and equipment.

Getting to Work

The canal boat crew could vary, but at the very least, it included a captain, a tiller, and mule driver. Very often, the family of the Canal boat operator was on board to help with the daily routine. Often small children were called into service as mule drivers. One woman told of her experience as a mule driver on her father’s boat. Madeline Free Rilleria said, “I loved the animals,

and they loved me, and they used to cry for me and whinny every once in a while, when they knew I was getting tired and then I would crawl up on their backs and make a bed on there.”1

A day on the Canal started at 3:30 a.m. with grooming the mules and getting them ready for the day’s journey. Some boatmen liked to feed their animals a ration of food before starting the day; others liked to get the mules moving before feeding them on the towpath with a feedbag. After harnessing the mule team was done, the captain would toss the towline to a helper on the towpath, who would attach it to the mule team.

Once they started, the crew would take turns at the tiller while someone cooked breakfast. Often, boat captains, who were confident in their mule teams, could leave them unattended to continue their towpath journey while the mule drivers took a break. Some captains were not lucky, and their animals would nibble greenery along the way. This annoying habit was called bushwhacking, a term generally used for clearing a path; its use seems appropriate here.

At the end of the day, around 10:00 pm, the captain would stop at a stable. Stables were located near locks and at other points along the canal. Some canal towns, like Uhlerstown not only offered a stable but blacksmith and boat repair services along with food and other supplies.

Once the harnesses were removed, most mules liked to have a good roll (a characteristic they are well known for), scratching and stretching before their evening repast and rest.

Caring for the mules

The value and importance of this equine cannot be understated. Mules played an essential role in the boatman’s success, and canallers ensured their animals were well cared for, including

regular feeding as they walked the towpath, watering, grooming, and farrier care.

And to keep everyone honest, an SPCA inspector would travel the length of the Canal inspecting the condition of the mules. One boatman recalls, “You didn’t dare to be mean to your animals on the Delaware. They had a woman down there, she’d make you stop the mules and lift the collar; and, if there was a sore on his shoulder, you had to take that mule out, you couldn’t use him. She was all through the Delaware. You never know when you’d run into her.”1

A Most Noble Creature

Historically, mules have worked tirelessly for us. They ask little. They are easy keepers and very loyal to their owners. Once they bond with you, you have a friend for life. Mules are also

quick learners, so working with a mule requires consistency. When they know what is expected, they will provide hours of service.

Studies show mules are generally more intelligent than horses or donkeys. This intelligence means they will not do anything to harm themselves and they can be protective of their

owners. When handled and trained properly, they are gentle, loving members of a family.

Author Rinker Buck states, “A horse will pretty much respond like a dog to a master’s request; their first instinct is to obey. A mule says, at a difficult stream crossing or a narrow gate opening, “Now wait a minute here, let’s consider the safety of this.” That, too, comes from the burro side. Mules have a very strong feral instinct to protect themselves.” 2

So, mules may not dive off a steel pier with you, but they will be glad to stand by and cheer you on.